Searching for that “something else”? It starts with beauty

“Got to find the brightness in the soul

Not look outside to find out where we are

Oh, you we won't be satisfied

Until you make possessions of the stars”

Karl Wallinger, 1986

Part I: Fighting Dragons

I had the pleasure to visit Myanmar a few weeks back. I’d last been there in 1998. I didn’t get to see much of the country, to appraise the inevitable changes since that distant last visit. I was participating in a two-day workshop so it was arrive, travel to the hotel, attend the workshop and depart. Never mind.

The workshop was hosted by the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business and PeaceNexus, a Swiss-based Foundation. I’d been invited to share thoughts on ways to help communities and businesses work better together. There were many representatives from grassroots NGOs present and some business representatives.

I learned, from the perspective of those attending, that there are many positive developments in the country but that bad things are also happening. The country is opening up which everyone agreed is good but that, after fifty years of military rule, there is only a very weak legal framework in place to govern how new investments are undertaken. There is a desperate, ugly rush by some investors to get in there as urgently as possible to get their hands on the country’s vast natural resources, secure that first mover advantage, and make as much money as they can before things become more controlled. Land is being grabbed, factories are being dumped on communities, pollution is pouring forth, poisoning people and crops and there is little or no recourse. Conflicts are springing up everywhere.

The community and NGO response is to pursue litigation, despite the terribly weak legal framework. There was a pervasive sense of battle, of good versus evil, of gearing up for a long drawn out struggle in the face of adversity while the bad guys enrich themselves and create mountains of despair in their wakes, a sense of ‘What else can we do?” There were few winners on the community/NGO side. I heard many stories of really wicked behaviour by companies unconstrained by any meaningful legal requirements but clearly also unhinged from any moral sensitivity toward the rights and needs of others. The feeling I got was one of people bunkering down to save whatever could be saved in the expectation that much would be lost despite the righteousness of the battle. I left wondering at humanity and why it had to be so.

Though this particular situation in Myanmar is unhappy, I reflected that it’s not unique to the country, to what is unfolding every day, everywhere else in the world. It’s all about fighting dragons. Good people are fighting these dragons and expending vast reservoirs of energy and effort. It seems to be a gruelling battle-by-battle life, with much death and winners and losers (mostly the latter) and everything going downhill.

I was reminded of Rilke’s beautiful words that my colleague Julien Troussier had used to open his recent article.

“Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

What if our dragons could be loved? What might happen then?

“What?! Are you crazy?” I hear voices crying. “These are evil people, they’re not to be loved, they’re to be beaten, controlled.”

That is certainly one approach, the one adopted by campaigning NGOs the world over, but as I watch these good people bunkering down in Myanmar, as good people have bunkered down forever, elsewhere in the world, I’m left feeling that it hasn’t really worked.

The first campaigning NGOs emerged from the ashes of destroyed Nature at the end of the 1960s. They’ve (mostly) been doing extraordinary work ever since and but for their efforts, the world would be further down the hill than we are today. There have been some good wins. Despite all these efforts, still the world and all that live in it are in deep trouble. There is climate change and unprecedented species extinctions. There are so many environmental and social troubles that have arisen as a consequence of our dragons’ rapacious behaviour. We are in the poo, massively.

The response always seems to be to seek more money to fund more battles, more wars against more dragons, more companies. This seems to me to be a nonsensical response. We only have to look at history to understand that pouring more money into more battles and more wars only creates more misery and more wasteland. More, more, more of exactly the same thing that has failed to extricate us from the poo in the first place.

Yes, without the great work of NGOs, the world would be in a worse place but my point is that just doing more of the same seems illogical. Despite their Herculean efforts we are still racing toward greater than 6oC climate change, a point at which no large mammal can live on the planet. That doesn’t mean they’re useless or should be criticized. No, they should be loved and more than most for they kill themselves and are often killed, literally, at the battlefront. It’s a tragedy. We still need them at the front lines to fight the dragons but it does suggest we need something else, a clandestine, back-channel approach that helps the dragons to stop being dragon-like. Finding that “something else” has so far eluded us, at least at scale. But there may be lessons, if we can look up from the battle for a moment, that we could learn from other parts of life.

What else might we try?

Part II: The View from the Edge of Life

The work of Dr Rachel Naomi Remen offers some insight. Doctor Remen is a highly respected paediatrician. She has lived with Crohn’s disease since she was 15 years old and has spent many years of her life working with patients with terminal illnesses. Doctor Remen has written two beautiful books, Kitchen Table Wisdom and My Grandfather’s Blessings, both highly recommended. In the latter, she writes about the concept of healing and the wonder and possibilities of serving life.

“Few of us are truly free. Money, fame, power, sexuality, admiration, youth: whatever we are attached to will enslave us, and often we serve these masters unaware. Many of the things that enslave us will limit our ability to live fully and deeply. They will cause us to suffer needlessly. The promised land may be many things to many people. For some it is perfect health and for others freedom from hunger of fear, or discrimination, or injustice. But perhaps on the deepest level the promised land is the same for us all, the capacity to know and live by the innate goodness in us, to serve and belong to one another and to life.”

Rachel Naomi Remen, My Grandfather’s Blessings, p374

I wonder what enslaves us? Are the dragons wholly enslaved by that rapacious hunger for money that blows all else away? I don’t think so. They have children. They have other passions beyond counting their money. What about the NGOs that battle them? What enslaves them, for surely we are all mired in these battles for a reason? Do we serve these masters unaware? Could we step back from the battle to view different possibilities? The key question for me from Dr Remen’s prose is, “how do we serve life?” and it’s one that I’ve been grappling with for years. How indeed? Here, Doctor Remen offers more food for thought,

“The view from the edge of life is different and often much clearer than the way that most of us see things. Life-threatening illness may cause people to question what they have accepted as unchanging. Values that have been passed down in the family for generations may be recognised as inadequate, lifelong beliefs about personal capacities or what is important may prove to be mistaken. When life is stripped down to its very essentials, it is surprising how simple things become. Fewer and fewer things matter and those that matter, matter a great deal more. As a doctor to people with cancer, I have walked the beach at the edge of life picking up wisdom like shells."

Rachel Naomi Remen, My Grandfather’s Blessings, p325

Dr Remen’s words on the power of life-threatening illnesses to help us question what we have always accepted as unchanging are enlightening. Could these experiences from the world of human suffering help us grapple with our behaviour toward the environment, toward each other? Dragons are people too.

Climate change, unrestrained, represents a terminal illness for humanity, a cancer like disease drawing us to the very edge of our existence. The revered David Attenborough noted in 2013 that humans are a plague on Earth. As those dragons grab land and poison communities and the environment, they are only hastening their own demise. NGOs fight them, thank goodness, but still the disease progresses. Hitting the disease harder with stronger, more inspired attacks is one approach but really is just more of what has ultimately been unsuccessful so far; long drawn out battles are won but the war rages onwards, on ever expanding fronts. Most of us haven’t yet seen our situation from this edge of life perspective. We carry on doing what we’ve always done; following life-long beliefs about what is right and what is important. Companies act badly, NGOs fight them. Voila, it’s the way; it’s life, right?

We aren’t yet open to the lessons we might learn from those who have already seen the world from the edge of life. We are not yet walking the beach picking up wisdom. What might we do to change that, to listen?

Part III: Finding the Light of the World

Doctor Remen offers an avenue for exploration on this matter in an OnBeing interview with host Krista Trippet from 2005. Here’s a transcript of part of their discussion where she speaks about the light hidden deeply within all of us.

MS. TIPPETT: You recount this idea of the Kabbalah, which I had known, but — I don't know, I think maybe because you're a storyteller, it was very vivid for me. That — this idea that at the beginning of the creation, the holy was broken up, right?

DR. REMEN: Oh, the story of the birthday of the world, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Is that how he told it to you?

DR. REMEN: Yes, exactly. Actually, Krista, this was my fourth birthday present, this story. In the beginning there was only the holy darkness, the Ein Sof, the source of life. And then, in the course of history, at a moment in time, this world, the world of a thousand thousand things, emerged from the heart of the holy darkness as a great ray of light. And then, perhaps because this is a Jewish story, there was an accident, and the vessels containing the light of the world, the wholeness of the world, broke. And the wholeness of the world, the light of the world was scattered into a thousand thousand fragments of light, and they fell into all events and all people, where they remain deeply hidden until this very day.

Now, according to my grandfather, the whole human race is a response to this accident. We are here because we are born with the capacity to find the hidden light in all events and all people, to lift it up and make it visible once again and thereby to restore the innate wholeness of the world. It's a very important story for our times. And this task is called tikkun olam in Hebrew. It's the restoration of the world.

What resonates for me in Dr. Remen’s description of the Kabbalah is the idea that we all have part of the light of the world in us but that it is hidden very deeply. Again, I can hear voices shouting, “Nonsense! Military companies? Chinese companies? Bah!”

I would agree that in some the light is buried very deeply indeed but I’m nonetheless convinced that it’s there. I’m convinced because of the many examples I’ve seen working with The Forest Trust.

Part IV: The Angel

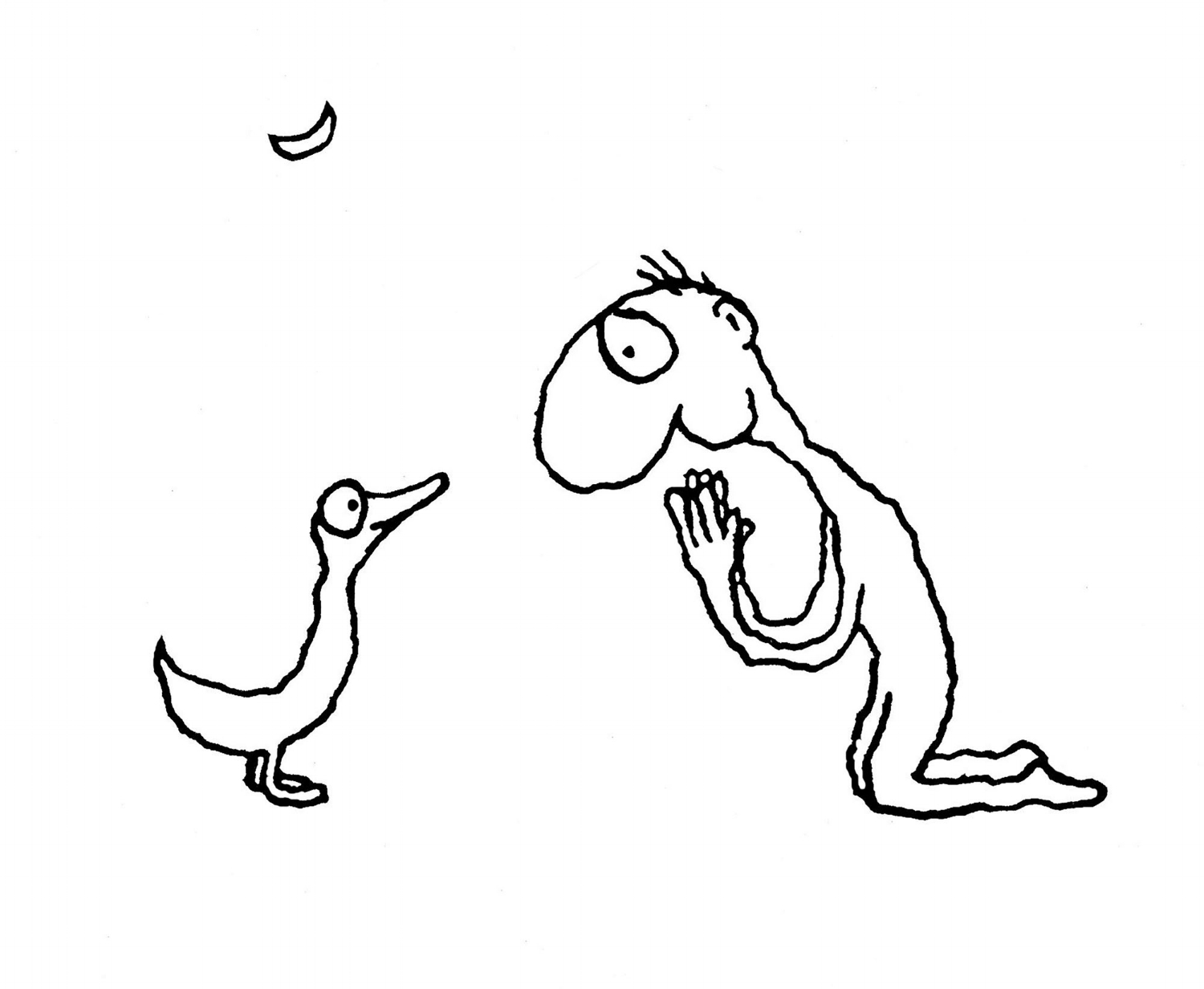

I’ve seen leaders of huge companies accused of all sorts of environmental and human rights abuses find their light and move to a different place, a place where they seek to redress troubles of the past in acts of restoration and healing. How have they done this? In my experience, these inspired company leaders have looked beyond the business case and have been touched by words from their family, by poetry, by art and philosophy. In the case of Wilmar, the world’s largest palm oil company, a simple philosophical cartoon played an important role in helping the leadership see their light. It was a cartoon by Australian philosopher Michael Leunig.

Having received the cartoon, the company Chairman found he was able to finally cross the final few steps over the bridge that he’d been travelling in his heart to announce wide-ranging policies to protect people and the environment.

Wilmar’s is not an isolated case. TFT works with thousands of companies. Conservatively we estimate that our work impacts over $1 trillion worth of stuff passing through global supply chains. We have many examples within TFT of companies being touched by more than just the business case to act. It is not niche.

Despite this and the obvious opportunity it creates, I’ve had campaigning NGOs mock me when I share the Wilmar story or other stories where we’ve seen companies leap into the unknown unexpectedly having been called to do so through means other than being shamed by NGO campaigns. Perhaps it’s the view from the frontline, from wizened soldiers? When discussing ways to get other companies to heed environmental or social concerns, some campaigners have scoffed, “What are you going to do? Send them a poem?” My answer has always been, “Yes, why not? If it helps.”

Part V: The Duck

Michael Leunig offers another beautiful metaphor for this light of the world. In 1990, Leunig published A Common Prayer. In the introduction, he drew a man kneeling before a duck to symbolise his ideas and feelings about the nature of prayer. Leunig asked the reader to bear with the “absurdity of the image” while he explains the picture.

“A man kneels before a duck in a sincere attempt to talk with it. This is a clear depiction of irrational behaviour and an important aspect of prayer. Let us put this aside for the moment and move on to the particulars.

The act of kneeling in the picture symbolises humility. The upright stance has been abandoned because the human attitudes and qualities it represents: power, stature, control, rationality, worldliness, pride and ego. The kneeling man knows, as everybody does, that a proud and upright man does not and cannot talk with a duck. So the upright stance is rejected. The man kneels. He humbles himself. He comes closer to the duck. He becomes more like the duck. He does these things because it improves his chances of communicating with it.

The duck in the picture symbolises one thing and many things: nature, instinct, feeling, beauty, innocence, the primal, the non-rational and the mysterious unsayable; qualities we can easily attribute to a duck and qualities which, coincidentally and remarkably, we can easily attribute to the inner life of the kneeling man, to his spirit or his soul. The duck then, in this picture, can be seen as a symbol of the human spirit, and in wanting connection with his spirit it is a symbolic picture of a man searching for his soul.

The person cannot actually see this ‘soul’ as he sees the duck in the picture but he can feel its enormous impact on his life. Its outward manifestations can be disturbing and dramatic and its inner presence is often wild and rebellious or elusive and difficult to grasp: but the person knows that from this inner dimension, with all its turmoil, comes his love and his fear, his creative spark, his music, his art and his very will to live. He also feels that a strong relationship with this inner world seems to lead to a good relationship with the world around him and a better life. Conversely, he feels that alienation from these qualities, or loss of spirit, seems to cause great misery and loneliness.

He believes in this spiritual dimension, this inner life, and he knows that it can be strengthened by acknowledgement and by giving it a name.

He may call it the human spirit, he may call it the soul or he may call it god. The particular name is not so very important.

The point is that he acknowledges this spiritual dimension. He would be a fool to ignore it, so powerful is its effect on his life, so joyous, so mysterious, so frightening.”

He further adds,

“Not only does he recognise and name it but he is intensely curious about it. He wants to explore it and familiarise himself with its ways and its depth. He wants a robust relationship with it, he wants to trust it, he wants its advice and the vitality it provides. He also wants to feed it, this inner world, to care for it and make it strong. It’s important to him.

And the more he does these things, this coming to terms with his soul, the more his life takes on a sense of meaning. The search for the spirit leads to love and a better world, for him and for those around him. This personal act is also a social and political act because it affects so many people who may be connected to the searcher.”

Leunig asks the key question that Dr Remen’s words challenge us to ponder:

“But how do we search for our soul, our god, our inner voice? How do we find this treasure hidden in our life? How do we connect to this transforming and healing power? It seems as difficult as talking to a bird. How indeed?"

He offers some ideas of possible paths.

“There are many ways, all of them involving great struggle, and each person must find his or her own way. The search and the relationship is a lifetime’s work and there is much help available, but an important, perhaps essential part of this process seems to involve an ongoing, humble acknowledgement of the soul’s existence and integrity. Not just an intellectual recognition but also a ritualistic perhaps poetic, gesture of acknowledgement, a respectful tribute.

Why it should be like this is mysterious, but a ceremonial affirmation, no matter how small, seems to carry an indelible and resonant quality into the heart which the intellect is incapable of carrying.

Shaking the hand of a friend is such a ritual. It reaffirms something deep and unsayable in the relationship. A non-rational ritual acknowledges and reaffirms a non-rational, but important, part of the relationship. It is a small but vital thing.

This ritual recognition of connection is repeatable and each time it occurs something important is revitalised and strengthened. The garden is watered.

And so it is with the little ritual which recognises the inner life and attempts to connect to it. This do-it-yourself ceremony where the mind is on its knees; the small ceremony of words which calls on the soul to come forth. The ritual known simply as prayer.

The garden is watered.

A person kneels before a duck and speaks to it with sincerity. The person is praying.”

Leunig’s Duck is accessible, and though it references god and prayer, it does so from a spiritual rather than a religious perspective, “the particular name is not so very important”. It’s universal.

These images of Angels, Ducks and light are important because from my work with TFT over many years, across so many different cultures, dealing with many different companies and within them many senior managers, workers, CEOs, Chairs, I’ve learned that profound and often completely unexpected change comes when people tap into this inner dimension, when they connect with their Duck, their soul, the light, their Angel. How they water their garden doesn’t matter. Some people pray, others walk, some find it in the shower, others on the toilet. The ‘how’ really isn’t important. What matters is that this ‘great struggle’, this striving to get close to your Duck leads to a better life for the searcher and for those around him. In the crazy hustle and bustle world where our perception of what’s important has been skewed to a more external view – wealth, status, fame, sexuality, power as noted by Dr Remen – my experience is, when talking to company people, that there is a very barren, dry, almost totally lifeless desert blocking most of us. It sits above our souls. Precious few gardens are being watered. Yet, my experience also tells me that there is a desperate, crying thirst for this nourishing water within people. Any pause from the day-to-day madness to discuss these matters, to speak of Ducks and light, finds urgent, craving resonance.’ Give me more!” Emotions are touched and it’s not uncommon to find tears where before there was anger. Touching these things waters people’s gardens and the discussions quickly come to essential points of humanity. It’s a lot easier to grapple with profound issues from that place than from a point of conflict, of battle with an NGO who has hung off your building or accused you of evil doings, justifiably or not.

I’ve come to wonder what might happen if we all spent more time striving to get closer to our Duck. Might we truly change the world around us?

Part VI: Super Cooperators – the Magic of Three Degrees

Professor Martin Nowak gives us encouragement that we might. Professor Nowak published the superb Super Cooperators in 2011. He is Professor of Biology and Mathematics at Harvard University and Director of the Program for Evolutionary Dynamics. He’s no dill. He is also one of the world’s experts on evolution and game theory and in Super Cooperators explains why cooperation, not competition, has always been the key to the evolution of complexity. We are successful as a species because despite much evidence to the contrary, we are excellent at cooperating with each other.

Super Cooperators deserves a complete review all on its own and it makes many wonderful points about humans and when and how we work best together. One point from the book that really resonates with me is when Professor Nowak shares the research findings from Nicholas Christakis of Harvard Medical School and James Fowler of the University of California that suggests that, “we are swayed by the moods of friends of friends, and of friends of friends of friends – people several degrees of separation away from us whom we have never met, but whose disposition and behaviours can ripple outward toward us through an intervening social network.”

I find this extraordinary in one sense but in another way, it’s not surprising at all. We’ve all felt the waxing and waning in a society’s collective mood. Professor Nowak shares that Christakis and Fowler found that, “happy people tend to be clustered together, not because they gravitate toward smiling people, but because of the way happiness spreads through social contact over time, regardless of people’s choice of friends”. He noted that they found that these findings extended to indirect relationships as well.

“Again, while an individual becoming happy increases his friend’s chances of smiling, a friend of that friend experiences a nearly 10 percent chance of increased happiness, and a friend of that friend has around a 6 percent increased chance – a three degree cascade of good humor. Thus your actions and moods – whether blue or jolly – affect your friends, your friends’ friends, and your friends’ friends’ friends.”

Nowak reports that Fowler and Christakis have done experiments involving complete strangers that found that altruistic, cooperative behaviour also spreads to three degrees.

This is hugely significant.

This means that if I act in a way that respects people and the environment, people three degrees of separation from me will be influenced, at least somewhat, to act in the same way.

We can see the significance of these findings if we do a little math. Imagine that I have 20 friends. Then consider that each of my friends has 20 friends of their own and on top of that, those people each have 20 friends too. That means the network of people, based on Christakis and Fowler’s findings that I can influence through my moods and behaviour is 8,000 people. Who knew? With 7 billion people on the planet, this means that if there were 875,000 people (just 0.0125% of the global population) acting in a way that respected people and the environment, that we could influence, at least in a small, 6% way, the behaviour of the entire global population.

This is of course a simplification. There are already more than 875,000 people around the world trying to live thoughtful, responsible lives but still we see destruction and loss happening on an unprecedented scale. This doesn’t render Christakis and Fowler’s findings void. It tells us there are of course cultural differences, geographic issues and scale issues that suggest we need more people spread around the world to be acting in a way that positively influences behaviour. There are societies where concern for people and the environment isn’t as well developed as it might be or where poverty creates an urgency just to live that leads to environmental and social catastrophes. Even then we’re only influencing them 10% at the 2nd and 6% at the 3rd degree of separation.

That said, if we consider the influence of the internet and social media, we can take the numbers to an interesting level. If instead of 20 friends, I could count 100 people that I influence because of Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn for example, and we imagine that they each have 100 people they influence and likewise that each of those 100 have their own 100 people then my network, at the 3rd degree of separation, expands to 1 million people! Then we only need 7,000 people (or 0.0001% of the total population) to start influencing the behaviour of everyone on the planet.

Breathtaking.

Again, the spread and location of these influencers needs to be across geographies and cultures and they really do need to act in a strongly influential way to just begin to influence people by 6%. For sure we need more than 7,000 key people but Christakis and Fowler’s findings strongly suggest that Margaret Meade’s assertion that a small group of people can change the world really is plausible.

What the findings convey is that if we focus on the only thing we can truly control in the world, our own behaviour, then we can, just by striving to live a good and responsible life, influence everyone around us, to some degree, to do the same thing. This is a scientific affirmation of what Michael Leunig suggests is the importance of striving to have a good relationship with your soul, with your Duck.

“This personal act is also a social and political act because it affects so many people who may be connected to the searcher.”

Part VII: Might we ourselves be the answer?

Professor Nowak’s notion of Super Cooperators, Michael Leunig’s Duck and his Angel, Dr Remen’s light of the world tell me that while we need our NGO friends to keep charging into the breech to fight those dragons that are not yet ready to be influenced, our path to a better relationship with each other and with the planet is to act according to the fundamental good that resides in each of us.

We each have to listen to our soul.

We can’t influence others’ behaviour for the better, we can’t call their soul forth to guide better behaviour, unless we have a deep relationship with our own soul, our own Duck. So we come back to Leunig’s beautiful introduction. Having such a relationship requires great struggle, it’s a lifetime’s work but again and again we see that striving to get close to your Duck brings a better life for the searcher and for those connected to the searcher.

This, I believe is our only chance at taking action on environmental and social concerns to sufficiently large scale to have the impact we need.

In her OnBeing interview with Krista Tippett back in 2005, Dr Remen described it beautifully:

DR. REMEN: And this is, of course, a collective task [the restoration of the world]. It involves all people who have ever been born, all people presently alive, all people yet to be born. We are all healers of the world. And that story opens a sense of possibility. It's not about healing the world by making a huge difference. It's about healing the world that touches you, that's around you.

MS. TIPPETT: The world into which you have proximity.

DR. REMEN: That's where our power is, yeah. Yeah. Many people feel powerless in today's situations.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, when you use a phrase like that just out of nowhere, "heal the world," it sounds like a dream. Right? A nice ideal, completely impossible.

DR. REMEN: It's a very old story, comes from the 14th century, and it's a different way of looking at our power. And I suspect it has a key for us in our present situation, a very important key. I'm not a person who is a political person in the usual sense of that word, but I think that we all feel that we're not enough to make a difference, that we need to be more somehow, either wealthier or more educated or somehow or other different than the people we are. And according to this story, we are exactly what's needed. And to just wonder about that a little, what if we were exactly what's needed? What then? How would I live if I was exactly what's needed to heal the world?

How would I live if I was exactly what’s needed to heal the world?

I contend that you would live in a way that inspires others to follow your lead. You would live according to your soul’s guidance and wisdom, according to your fundamental beliefs and values. And if people see you doing that, they might be tempted to explore their own possibilities to do so too.

And here I come back to my experiences with TFT, with Wilmar and other company leaders who have found that inner dimension in their lives and set out to live according to its voice. In doing so, others have followed, they have been influenced. The struggle continues, it’s on-going, much remains to be done but it gives me hope that we actually already have a way of scaling up beyond the “attack them one by one” scenario that inevitably bedevils NGOs, and all of us. It seems to me that the “something else” we’ve been searching for is literally staring us in the face.

Part VIII: It Starts with Beauty

On my way to Myanmar, I transited through Zurich airport. As I passed through the gate, I looked ahead down the ramp to see an advertisement. It was for Camel cigarettes. There was a picture of something exotic, I don’t remember what exactly, and the words “It starts with imagination”.

This annoyed me greatly. Both my father and mother and many of my friends and colleagues have died from smoking related cancer. My father smoked Camel cigarettes for many years before switching to Marlboro to drive the final nails into his coffin, lung cancer taking him a few weeks after his 68th birthday. The sign offended me and I wondered at their audacity to try to enslave people with the idea that you could link their death sticks to the inspiration of one’s imagination.

As I settled into my seat on the plane, I tried to think of what else, what more positive things other than smoking, might be started with one’s imagination. It seemed to me that helping people connect to their souls really might start with helping them to pause a moment and appreciate the beauty that’s around them. Yes, that our path to a better relationship with each other and with Nature, to our Ducks, to our Angels, to the light of the world might start with the simple act of getting people to stop, to look up and admire beauty.

That beauty could be in the form of a picture, a movie, a poem, music, art, walking in Nature, sitting looking out a window, being with friends and family, holding the hand of a loved one, looking into the eyes of a being that loves you. Again, it doesn’t matter. The simple act of pausing from the pursuit of all that enslaves us might allow us to pick up the wisdom on the beach at the edge of life that Dr Remen so beautifully describes. Such wisdom, afforded to those suffering terminal illness, might be the gift we all need to change the way we live, the way we interact with each other and the planet. In My Grandfather’s Blessings, Dr Remen shares the story of one of her patients.

“One of my patients who survived three major surgeries in five weeks described himself as “born again”. When I asked him about this, he told me that his experience had challenged all of his ideas about life. Everything he had thought true had turned out to be merely belief and had not withstood the terrible events of recent weeks. He was stripped of all that he knew and left only with the unshakable conviction that life itself was holy. This insight in its singularity and simplicity had sustained him better than the multiple, complex system of beliefs and values that had been the foundation of his life up until this time. It upheld him like stone and upholds him still because it has been tested by fire. At the depths of the most unimaginable vulnerability he has discovered that we live not by choice but by grace. And that life itself is a blessing.”

Rachel Naomi Remen, My Grandfather’s Blessings, p325

Such wisdom might help us to understand that destroying forests isn’t OK. Such wisdom might help us to understand that having child slaves in India break rocks for our cobblestone driveways isn’t OK. That pouring plastics and chemicals into the oceans isn’t cool. That continuing to burn fossils fuels makes no sense. That shooting endangered wildlife isn’t what we should be doing with our day. That it’s not OK to grab community land. And so on…

If we can see the beauty in the smallest of snails, the invisible bacteria and protozoans that surround us, just the thought of a wilderness we will never see, in the sunrise or sunset, in the furrowed brow of an exhausted soul torn by war, by poverty or even greed, might we not act in a way that better protects them? That loves them? If we can pause a moment and strive to appreciate the beauty in everything around us, surely we will approach our relationship with it, with ourselves and with each other in a completely different way?

Beyond protecting things, might we start to act in a way that heals the damage of the past? It’s great to say I’ll not do X or Y anymore, once you understand their negative impacts, but what of the damage already caused? Stepping beyond protecting to become a healer of past ills is urgently required too. We’re never going to get atmospheric carbon below 400ppm unless we actively remove carbon from the atmosphere. We can’t save wildlife unless we restore habitat. Polluted rivers need rehabilitation. There are many cases where humans have acted as healers. Can we take those to scale?

Beating up on people can get them to change but it starts from a place of angry judgement – I’m good, you’re not - so it can never flourish, it can’t inspire change at a grand scale, it can’t go viral. It’s something to shy away from. It doesn’t start with compassion. It doesn’t start with beauty. It starts with destruction and is an understandable response to the despoiling of Nature. But it can only battle forth. It’s as hard and tiring on the person doing the beating as the person being beaten. There is no love or joy in such relationships. More often than not, the target person or company does change, eventually and usually after much destruction, stress and tension, but everyone else who might also change scuttles away into the darkness where they’re safe with their friends, hiding from the light and pursuing death in the shadows.

My colleague Julien Troussier puts it thus, “By seeing and connecting with what is beautiful and alive in Nature, in others (even the CEO dragons) and in you, rather than fighting and judging the dark and ugly, you call forth the creative power of the soul in you, others and eventually Nature. And you are then more likely to see the darkness and brokenness with compassion too, as the inevitable, perhaps necessary stumble towards wholeness. The vessel had to be broken as part of the unfolding creation, of life.”

Dr Remen expands on her Grandfather’s story of the light of the world in My Grandfather’s Blessings:

“We restore the holiness of the world through our lovingkindness and compassion. Everyone participates. It is a collective task. Every act of lovingkindness, no matter how great or small, repairs the world.”

She adds that, “The name Kabbalah uses for this collective work is Tikkun Olam, we repair and restore the world. Everything in life presents us with this opportunity. It invests all our struggle with a deeper meaning and deepens all our joy.”

I find myself feeling some gratitude to the slick, highly paid marketing agency that came up with the “It starts with imagination” nonsense for Camel. They’re a great inspiration in many ways. If you understand how successful they’ve been in turning people toward death – surely an action that is deeply counterintuitive for most of us – might we use the power of their manipulation to turn people toward life?

Surely we must turn people to life, to its radiant beauty? If we can break free from the things that enslave us, might we not break free from the path of death and instead begin to serve life?

Beauty seems to me to be the answer, the “something else”.

Instead of looking at people as evil, what if, instead, we could woo them out from the shadows and into the beauty of the sunrise? What if we could whisper their Ducks to emerge and be fully present in their lives?

The only way we can do that is to lead by example. There is absolutely no way we can help call forth the Duck, the light, the Angel in others, unless we’ve found it and have a relationship with the Duck, the light or the Angel – remember, the name isn’t so important – in ourselves. The mathematical proof from Professor Nowak tells me that if I act in a way that serves life, I can influence maybe 1 million people to serve life too. If I act in a way that heals and restores, others might follow. And if they follow, the people they know might come into the light too and so on and so on.

Isn’t living true to our inner wisdom, to the teaching of our souls, to the voice of the Duck the only way to truly serve life and bring about the change we need? If we can connect to the beauty of the outer world, we can more easily connect to the beauty, the light, the Angel and the Duck of our inner world.

It starts with beauty.

We don’t have to of course and many of us are so enslaved by our pursuit of wealth, power, fame etc. or our pursuit of more people to beat up because we’re right and they’re wrong, that right now, I’d have to conclude that we’re not going to make it. We’re all so stuck in the belief that ‘the other side’ are nuts and that they’re to be resisted, fought, defeated. More money for more wars please. While we choose to stay in that place firing rockets at each other, there is no place for Ducks.

The thing is, it’s a choice. Going after money, fame, glory can bring great reward – comfort, prestige, power. But as Leunig notes, striving to get closer to your Duck, to have a relationship with it, involves suffering and great struggle. It’s much harder but many would argue it brings deeper, more satisfying reward. One way serves death and the other, the way of the Duck, serves life.

It’s a choice.

And here I’m reminded by the words from another piece of ancient wisdom. British author Lindsey Clarke retells Wolfram von Eschenbach’s story of Parzival and the Holy Grail in his 2001 book Parzival and the stone from heaven. Eschenbach’s chivalric myth dates from the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries and tells the story of a young knight and his search for fame and prestige, only to find he has created vast wastelands in his wake. Finally, after an epic battle, he finds compassion for his wounded Uncle and in asking, simply and beautifully, “What ails thee Uncle?” he releases the power of the Grail to heal and to bring light to the world.

There is much in the Parzival story that resonates beautifully with Dr Remen’s telling of the Kabbalah, with the wisdom she finds at the edge of life and in Leunig’s simple wonder of a man kneeling before a Duck. Clarke concludes his telling of the Parzival story with these beautiful words:

“And if there was a war in heaven once, then we who are neither wholly good nor wholly bad, we who consist of both shadow and of light, we sad wounded creatures standing between heaven and earth, striving to be whole – can, if we are truly human, choose to be among the healers too”

Lindsey Clarke, Parzival and the stone from heaven, p206

We can, if we are truly human, choose to be among the healers too.

So…the path seems clear to me. We each have to water our own gardens, each of us who is neither wholly good nor wholly bad, must strive to see beauty in everything and act with compassion according to the wisdom of our Ducks. If we can do that, we don’t need to be famous, we don’t need to be rich, we don’t need to be a powerful CEO and we don’t need to count our scars from battles with each other.

If we can do that and be true to our own Duck, to listen to the wisdom of our soul, we might find we have a better life and we might just whisper forth the Duck in others. Then, slowly, imperceptibly at first, perhaps even inadvertently, we might start changing things in the world for the better. That would indeed be something else.